Celmira, an eulogy to my grandmother (1929-2017)

La estás viendo cerca de la ventana, y su mirada te señala a un adentro, y te das cuenta de que su memoria está fragmentada en al menos dos partes: entre los

recuerdos de una larga vida que parecen rodarse como dados fuera de todo eje temporal, y un abismal presente desligado del pasado, que no es otra cosa que eso que llaman olvido.

Una noche, en aquella época en la que vivía con tu hermana, tuvo uno de esos episodios en que su mundo parecía caerse en el vacío de aquel presente desligado, y

entonces preguntó: “¿Yo por qué estoy así?”

You watch her near the window, and her gaze points you to an inside, and you realise that her memory is fragmented in at least two parts: between the memories of a

long life that seems to be a rolling dice out of every temporal order and an abysmal present detached from the past, which is nothing more than what they call oblivion.

One night, during that time when she was living with your sister, she had one of those episodes in which her world appeared to be falling into the void of that

detached present, and then she asked: “How come I'm like this?”

Frente a ella habitas entonces entre un pasado que vive desencadenándose y un vacío temporal. Sabes así que la temporalidad de la vida consiste en una libre superposición de tiempos en los que eres tanto adulto como niño. Por eso te recuerda, pero pregunta si ya has conocido a una de tus sobrinas, pues en su mente tú te fuiste del país hace muchísimo tiempo. Y aun cuando la línea temporal no concuerda, el sentimiento es correcto: hace mucho que te estás yendo, hace mucho que te fuiste. Entonces te mira y te dice: “uno se muere y usted ni se da cuenta”. La muerte del otro es en la mayoría de los casos un evento postergado del que nos damos cuenta con cierto retraso. Como la luz de las estrellas.

So, before her, you dwell between an unlinking past and a temporal void. You know that the temporality of life consists on a free overlapping of times, in which you’re both a grown-up and a child. That’s why she remembers you, but asks whether you’ve met one of your nieces or not, for in her mind you left the country a long time ago. And while the timeline doesn’t match, the feeling is correct: it’s been a long time since you’re leaving, it’s been a long time since you left. Then she looks at you and says: “If one dies, you wouldn’t even know.” The death of others is in most cases a postponed event, of which you only know after certain delay. Like the light of the stars.

Es cierto que, en su mente, incluso habiendo vivido algunos adelantos tecnológicos, el mundo nunca fue global, nunca estuvo tan conectado. El mundo era apenas un jardín y un patio en el que se les daba de comer a los puercos, o a los conejos, y donde los niños disfrutaban del arroz pegado que quedaba en el fondo de la olla.

It’s true that in her mind, despite having lived through some technological advancement, the world was never global, it was never that connected. The world was just

a garden, and a patio in which pigs were fed, or the rabbits, and where children enjoyed the stuck-on rice from the bottom of the pot.

La estás viendo cerca de la ventana, y su mirada te señala a la espera, y al recuerdo de aquella vez que burló a la muerte cuando un bus la arrolló. Te das cuenta

de que desde aquel entonces ya no caminaba tanto como antes. En tu memoria ella caminaba. Y mucho. Siempre era joven, siempre sin canas. Después adquirió ese estilo tierno de pingüino y se volvió

vieja. Pero extrañas su caminar.

You watch her near the window, and her gaze points you to the wait, and to the recollection of that time when she outwitted death after a bus ran over her. You

realise that ever since then she didn’t walk as much as before. In your memory, she walked. A lot. Always young, always without grey hair. Later she got that cute penguin style and went old. But

you miss her walking.

Ahora ves sus manos. Arrugadas, secas, hermosas. Las mismas que te cargaron cuando eras un bebé. Las que cuando eras niño te acariciaron el pelo, te dieron de

comer, y cocieron o arreglaron tus ropas en aquella vieja máquina Singer. Las que aplicaban inyecciones. Las mismas que criaron siete hijos, y gozaron y sufrieron con ellos, y cuidaron a un

esposo agonizante de cáncer. Aquella vez cuando viste a tu abuelo antes de morir, te diste cuenta de que, así como las estaciones previamente se anuncian con un aroma que de repente se te cruza,

un conocimiento que sólo adquiriste desde la distancia en otro continente, también así la muerte natural se anuncia con un olor que circunda a quien la espera. Pero este olor no sabe atravesar

océanos ni montañas, sino que yace cerquita de quien espera la tierra. Por eso esta vez no hubo nunca un olor que te alcanzara en la lejanía, sólo la paulatina certeza de que la partida de tu

abuela estaba anunciada. Porque ella lo supo antes – así te contaron – cuando se reclinó sobre su silla y casi se cae. Como si estuviera asomándose a algo que sólo ella podía ver. Como si ella

misma determinara su destino. Y así fue.

Now you watch her hands. Wrinkled, dried, pretty. The same that hold you as a baby. The ones that when you were a boy stroke your hair, fed you, and sewed or fixed

your clothes in that good old Singer sewing machine. The ones that applied injections. The ones that raised seven children, and rejoiced and suffer with them, and took care a husband agonising of

cancer. That time when you saw your grandfather before passing away, you realised that just like the seasons announce themselves early with an aroma that suddenly crosses you, a knowledge you

only acquired from the distance in another continent, so too the natural death announces herself with a scent that surrounds he who waits for her. But this scent doesn’t know how to travel across

oceans or mountains, because it lies very close to whom awaits the earth. Hence, there was no scent that reached you in the distance, just the gradually increasing certainty that her passing was

announced. Because she knew it before, or so you were told, when she reclined over her chair and almost hit the floor, as if she was looking to something only she could see. As if she was

deciding upon her destiny. And she did.

Tantas cosas pasaron alrededor de ella, que ya no saben si tus recuerdos son los tuyos o los de tus padres o hermanos, o de tus primos, o de tus tías, pues tus tíos

siempre los recuerdas lejos. Todos los tíos siempre están lejos de algún modo, igual que tú, a veces…

So many things happened around her that you no longer know whether your memories are yours or your parents’ or siblings’, or your cousins’, or your aunts’, since

you always remember your uncles being far away. All the uncles are always somehow away, just like you, sometimes…

Entonces te asaltan conversaciones del pasado. Cuando te dijo que se casó con un mulato siendo una “vaca”, pues tenía algo así como 23 años, o sea muy vieja para

aquel entonces. Así mismo, ella acuñó un nuevo significado del verbo ‘molestar’, como cuando contaba que su mulato la “molestaba” mucho. Esa fogosidad sexual parece formar parte de toda tu

familia. Ustedes “molestan” mucho.

Then you’re overcome by conversations of the past. When she told you, she was a “cow” when she married a mulatto, for she was about 23, that was too old back then.

Likewise, she coined a new meaning of the verb ‘bother’, like when she told how her mulatto used to “bother” her a lot. That kind of sexual verve seems to be part of your whole family. You all

“bother” a lot.

Pero, sobre todo, recuerdas la rutina del café después del almuerzo. Jamás faltaba. Por eso fue la encargada de la iniciación en la cafeína. O al menos es lo que

recuerda tu hermano, pues tú no tienes memoria de tu primer café, sólo de la tostada remojada de tu abuelo en el café hecho por ella.

But above all, you remember the coffee after lunch. It never missed. That’s why she oversaw the initiation into caffeine. Or at least, that’s how your brother

remembers, since you don’t have recollection of your first coffee, only of your grandfather’s wet toast in the coffee she made.

Y en ese disfrute del café, ahora que la ves sentada cerquita a la ventana, reconoces en ella el rostro de tu madre y sus demás hermanos y hermanas, y también un poco de tu propio rostro. Madre en madre, nieto en abuela. Por eso lloras y te duele mucho, pues sabes que ahora una generación completa de tus antepasados ha desaparecido.

Pero también siempre has sabido que todos los trozos de sufrimiento que han acompañado tu vida llevan la insignia de una risa y un gozo, como una especie de objeto serio y pulcro que al darle la

vuelta lleva inscrito un chiste sobre sí mismo. Y así extrañas la sonrisa y el son de la risa de tu abuela. La misma que si era muy intensa, algo que muchos querían incitar y ella evitar,

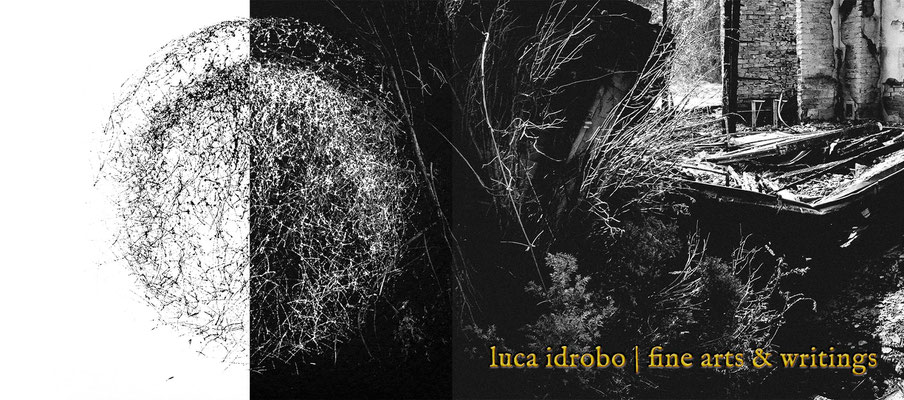

provocaba un aluvión de aguas menores y la carcajada de los contertulios. Y ahora que ríes y lloras al mismo tiempo, escribiendo y mirando las fotos que le hiciste, sabes que la amaste, y que

ella nos amó a todos.

And in that joy, now that you watch her so near the window, you recognise the face of your mother and the rest of her siblings, and a bit too of your own face. Mother in mother, grandson in grandmother. Hence you cry, and it hurts you deeply, because you know that an entire generation of your ancestors has vanished.

But you’ve always known that all the pieces of suffering that have accompanied you in life carry the sign of laughter and joy, like a sort of earnest and neat object that when you turn it around

it reveals an engraved joke about itself. And so, you miss your grandmother’s smile and the sound of her laughter. The same that when it got intensified, something that many wanted to incite and

she to refuse, it provoked some pee and the laughing of the companions. And now that you laugh and cry at the same time, writing along the photographs you took from her, you know that you loved

her, and that she loved us all.

¡Gracias abuelita!